Landscape theme and variations, 1963 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Here McCahon once again paints on panels. The overall affect is in a storytelling, narrative style, like the pages of a book unfolding. Different aspects of quite dark landscape are depicted, with muted tones of browns, ochres, greens, yellows, and shades of whites dominating. McCahon is speaking to the viewer with paint; these panels seem alive and vibrant, more alive than the real thing, perhaps. The tones and shadings are uniform, and there is an overall raw edginess to the work.

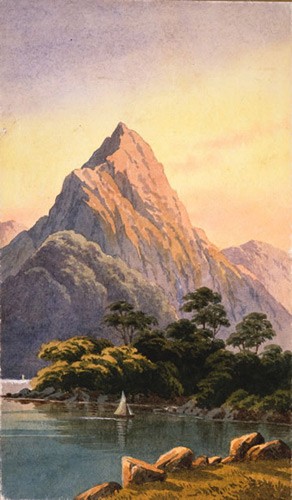

Six days in Nelson and Canterbury, 1950

In in works, McCahon loved to convey a feel of place, a depth of connection to the land. The above work, has a haunting, isolated ambience about it. Mccahon has captured both the base, primal beauty of the land as well as its definitive raw essence. Once again, the work is sectoned, the works in pared back frames, this is a work that is about the narrative of landscape painting.

Muriwai, A Necessary Protection Landscape, 1972 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

For a time McCahon had a studio based out at Muriway Beach, a rugged, wildly beautiful West Auckland beach As the title suggests, this is a painting about the endangered environment, a concern that often underpinned McCahon's work.

This actually depicts the gannet colony at Muriwai Beach, and it seems that MCCahon was implying that the this was under threat. The colours used are stark and bold, whilst the brushstrokes are

loosely rendered. McCahon was also concerned about humankind's impact upon the land, which was an emerging issue back in the 1970's. Also of concern in this era was nuclear disaster, and this was also something that McCahon tried to convey in his later works. The blacks, whites, yellow is harsh and decisive, the black rectangles cutting into the land, perhaps to suggest intrusion, interference and confusion.

Large Jump, 1973 Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

"I saw an angel in this land."

McCahon had a deep interest in religious motifs, and the above two works could also be read from a religious or Christian point of view. McCahon was a Christian, and in his earlier works painted Christian/biblical motifs into his landscapes. As the title would imply, this painting has a religious aspect to it, and also, the background is luminous, creating a highly effective contrast against the black.

McCahon wrote in 1971:

“I am not painting protest pictures. I am painting about what is still there and what I can see before the sky turns black with soot and the sea becomes a slowly heaving rubbish tip. I am painting what we have got now and will never get again. This is one shape or form, has been the subject of my painting for a very long time.”